Carl Sandburg’s poem “Chicago” turned 100 the other day. That is, March 2014 marked the 100th anniversary of its original publication in Poetry, along with eight other “Chicago Poems.” Two years later, these poems would all appear in Sandburg’s Chicago Poems (Henry Holt, 1916) and for the rest of his long life, Sandburg would be a famous poet, a fame undergirded by his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (Harcourt Brace, 1939) and his activities as a preserver of American folk music, in The American Songbag (Harcourt Brace, 1927) and various recordings based on it. With Vachel Lindsay and Edgar Lee Masters, Sandburg formed a triumvirate that Poetry founder/editor Harriet Monroe used to build the poetic wing of the Chicago Literary Renaissance.

One can only imagine her delight on receiving “Chicago” in the mail. If she’d been looking to start a literary revolution in the Midwest, she’d just been handed her manifesto, and it is small wonder she gives “Chicago” pride of place in the March 1914 issue. For here is a massive middle finger to the cultural establishment of the East Coast—New York City mainly, but I presume Boston and Philadelphia as well—up which Monroe can run her mutinous flag, though Sandburg’s poem works not by attacking these strongholds but by absorbing the dismissive insults hurled at his Midwestern literary outpost. “Hog Butcher for the World, / Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, / Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler; / Stormy, husky, brawling, / City of the Big Shoulders:” Sandburg seems to inhale these sordid conceptions of Chicago and get off on them, like some powerful drug.

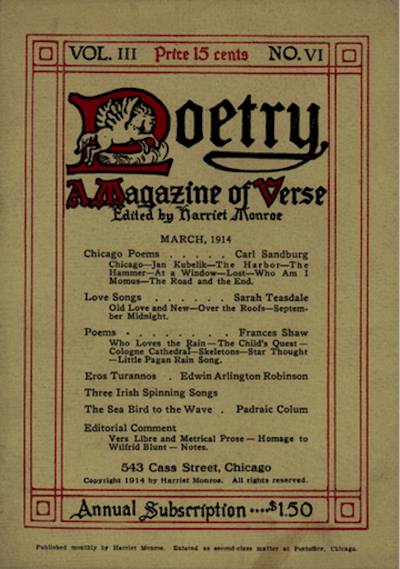

Like Whitman, Sandburg in “Chicago” is an enthusiastic cataloger, drawing a kind of sustenance even from the tragic elements of the particular cityscape he chronicles. The focus on certain facets of urban experience—factories and machines, barrooms and skyscrapers, immigrants and politicians, shopgirls and prostitutes—tends to get Chicago Poems classed as a kind of proto-social realism, though the defiant exuberance Sandburg derives from these subjects throughout makes me wonder if “Chicago” isn’t better thought of as a late outburst of American symbolism. In my pamphlet Quintessence of the Minor (Wave, 2010), I posited 1914 and the First World War as the tail-end of English and American symbolism, and with its gaslit “painted women,” “Chicago” would have fit right in with this scheme. In its way, Chicago Poems is a flâneur’s book of the city, much like Arthur Symons’s London Nights (Leonard Smithers, 1895) or John Davidson’s Fleet Street Eclogues (Mathews & Lane, 1893). We tend not to think of Sandburg like this, but it’s not so farfetched, for his city wasn’t immune to the symbolist atmosphere at the turn of the Twentieth Century. One of the most important American symbolist magazines, The Chap-Book (1894-1898), came out of Chicago, before merging into The Dial, which itself remained in Chicago until its 1918 move to New York. A glance at the cover and typography of the March 1914 issue of Poetry, moreover, reveals a decidedly symbolist bent; the hard lines we associate with later modernism had yet to infiltrate the magazine’s visual aesthetic. I raise this point not to be pedantic but rather because considering “Chicago” and Chicago Poems in terms of symbolism instead of social realism brings Sandburg’s modernity into greater relief.

The book as a whole is divided into seven sections—“Chicago Poems,” “Handfuls,” “War Poems” (1914-1915), “The Road and the End,” “Fogs and Fires,” “Shadows,” and “Other Days” (1900-1910)—and I imagine the 55-poem title section, beginning with “Chicago” itself, might be taken as a single fragmentary long poem. These poems provide a fascinating window into the dawn of the modern city, with motor-cars jostling the horse-drawn wagons, ice handlers existing side-by-side with the “electric fire” of lightbulbs. There is much great poetry here. “The Right to Grief,” for example, laconically dedicated “To Certain Poets About to Die,” concerns the death of the three-year-old daughter of a “stockyard hunky”—what a phrase!—whose job it is to sweep hog blood off the slaughterhouse floor for $1.70/a day. After describing the hunky’s profession and the terms of the installment plan on which he has purchased the coffin, Sandburg writes:

The hunky and his wife and the kids

Cry over the pinched face almost at peace in the white box.

They remember it was scrawny and ran up high doctor bills.

They are glad it is gone for the rest of the family now will

have more to eat and wear.Yet before the majesty of Death they cry around the coffin

And wipe their eyes with red bandanas and sob when the

priest says, “God have mercy on us all.”I have a right to feel my throat choke about this.

You take your grief and I mine—see?

There’s a brutal frankness to this fourth line that destroys any sentimentality to this scene, even as Sandburg professes to be moved to tears. The line is not a condemnation but merely an assertion of the calculus by which the poor are compelled to live, so simply stated as to seem artless yet it’s no mean feat to perfectly construct a line of such length. I like the last line quoted above in particular because it seems so modern, or postmodern, like something out of a John Ashbery poem (say, from “Grand Galop”: “Ask a hog what is happening. Go on. Ask him.”). Sandburg is really up to something new here, and “Chicago Poems” is studded with such moments.

The city’s welter of ethnicities is of particular fascination to Sandburg. On first perusing the table of contents to Chicago Poems and seeing the title “Nigger,” I naturally turned straight there, wondering how he would acquit himself on this topic. I have to admit, I found the first line arresting, coming from a white American poet in 1914: “I am the nigger.” I feel like the rest of the poem doesn’t quite live up to this; that is to say, his singing, dancing, banjo-strumming black man isn’t quite as real as, say, his “crowd of Hungarians under the trees with their women and children and a keg of beer and an accordion” several pages earlier. Another way to put it is that “Nigger” quickly gives way to the sort of sentimentality we’ve seen him undercut in poems like “The Right to Grief,” “heaving life of the jungle / brooding and muttering with memories of shackles,” that type of thing. But I’m inclined to give Sandburg the benefit of the doubt here, given the context in which he’s writing 100 years ago. The same issue of Poetry that opens with “Chicago,” for example, also closes with a ridiculous bit of business by Ezra Pound, “Homage to Wilfred Blunt,” in which he goes well out of his way to make an anti-Semitic remark, and too, 50 years later, Sandburg will be the first white man honored by the NAACP as a “Major Prophet of Civil Rights in Our Time.” Let’s not forget, moreover, the 1919 Chicago Race Riot—so-called, though it seems to have been largely a case of white violence against blacks—that will explode a mere three years after Chicago Poems is published. Chicago of the nineteen-teens was not a propitious environment in which to promote understanding and tolerance, and even Sandburg himself had to start from somewhere.

Another poem I was struck by among the “Chicago Poems,” “Muckers,” depicts “Twenty men” watching the titular group of laborers digging a ditch in the muddy clay soil in order to lay “the new gas mains.” Like any of several Sandburg poems, “Muckers” ends in a moment of perspectival irony: “Of the twenty looking on / Ten murmur, ‘O, it’s a hell of a job,’ / Ten others, ‘Jesus, I wish I had the job.’” I recalled these lines frequently in thinking about the relationship between Carl Sandburg’s “Chicago” and Lew Welch’s “Chicago Poem,” for here we have two poems looking at the same city and drawing polar opposite conclusions. In “Chicago,” Sandburg defies readers to “Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.” In Welch’s “Chicago Poem”:

Proud people cannot live here.

The land’s too flat. Ugly sullen and big it

pounds men down past humbleness. They

Stoop at 35 possibly cringing from the heavy and

terrible sky.

Part of the difference here, of course, is time. Welch’s poem is published in 1959, some 45 years after Sandburg’s, in the second issue of Calvin Kentfield and William H. Ryan’s Contact: The San Francisco Collection of New Writing, Art, and Ideas (which incidentally shares its name with a little magazine of the '20s and '30s co-edited by one of Welch’s poetic heroes, William Carlos Williams). Welch’s Chicago is Beat, and not in the beatific sense. The old organic parts of urban life—horses, ice handlers—are long gone, and the gas mains laid by Sandburg’s “Muckers” merely serve as the source of torment for Welch in the form of industrial pollution:

In the mills and refineries of its south side Chicago

passes its natural gas in flames

Bouncing like bunsens from stacks a hundred feet high.

The stench stabs at your eyeballs.

The whole sky green and yellow backdrop for the skeleton

steel of a bombed-out town.

Another difference is place. “Chicago Poem” is published after Welch has left Chicago for what by the late '50s are the greener poetic pastures of the San Francisco Bay Area. He is shaking the dust from his shoes, as it were, having made good on his threat: “I’m just going to walk away from it.” Perhaps another way to think about these differences of time and place would be to suggest that in Sandburg’s poem Chicago is in a state of becoming while in Welch’s it has already happened and now has entered a state of decay. “You can’t fix it,” Welch writes. “You can’t make it go away.” Unlike the high Sandburg receives even from the city’s sordid aspects, Welch displays a fundamental ambivalence toward the urban landscape; as he writes in his preface to Ring of Bone (Grey Fox, 1973/City Lights, 2012), the three characters in his poetry are “The Mountain, The City, and The Man” and though “it appears he will always need both,” one suspects the man would rather be “back on the Mountain.” Indeed, Welch spends a full third of his poem (four of twelve stanzas) outside of Chicago fishing and shooting quail, only to drive back to see “Chicago rising in its gases,” which is as great an image of an industrial city looming on the horizon as I’ve ever read.

In light of my earlier remarks, I can’t fail to note the presence of the word “nigger” in Welch’s poem, in what to me is its most opaque passage, picking up from the above-quoted “bombed-out town”:

Remember the movies in grammar school? The goggled men

doing strong things in

Showers of steel-spark? The dark screen cracking light

and the furnace door opening with a

Blast of orange like a sunset? Or an orange?It was photographed by a fairy, thrilled as a girl, or

a Nazi who wished there were people

Behind that door (hence the remote beauty), but Sievers,

whose old man spent most of his life in there,

Remembers a “nigger in a red T-shirt pissing into the

black sand.”

I’ll be damned if I know what Welch is on about in this latter stanza. I think at first I imagined the “It” in its first line referred to Chicago more generally; by the time we reach “that door,” however, it’s clear he’s still talking about the “furnace” of the previous stanza, so we remain somehow within “the movies in grammar school”—a digression within a digression. The oddness of this stanza is heightened by the phrase “in there,” for what are we to infer from this? That Sievers’ “old man spent most of his life” in the furnace? Or are we meant to pull back out of the digression, to the “mills and refineries” of two stanzas earlier? This question aside, why this particular memory of Sievers, which doesn’t say the word “nigger” so much as report it as speech? You got me. Is it simply to suggest that, in 1959, this is still how white people in Chicago speak? In a poem cataloging the details of a seeming whorehouse called “Jungheimer’s”—from the section of Chicago Poems called “Shadows” which is largely concerned with prostitution—Sandburg writes: “Tall brass spittoons, a nigger cutting ham.” The non-pejorative casualness of the usage here from the future Major Prophet of Civil Rights is far more disconcerting than the deliberate and self-conscious “Nigger” of the “Chicago Poems” section, and it’s worth noting that this is the only word by which African Americans are referred in Chicago Poems, as though there were no other term in the white Chicago lexicon. (Whereas we can contrast the appearance of, say, the word “dago” with the appearance of the word “Italian” in Chicago Poems.) Even the word “negro” never appears, and again, he’s clearly going for speech and slang; yet it wouldn’t surprise me if “nigger” were simply his (and indeed the) default term for a black person, as a white Chicagoan in 1914. In any case, again, I have no real idea what Welch is up to in this particular stanza, if not to foreground the intensity of racial prejudice against African Americans in Chicago.

In closing, we might note that this month (May 2014) is the 100th anniversary of another crucial work of American poetry which was of the first importance to Lew Welch: I mean, of course, Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, which City Lights has just brought out in a corrected centennial edition. Like Chicago Poems, Tender Buttons too has a symbolist connection, insofar as it was originally published by New York decadent Donald Evans’s small press Claire Maire. Besides Williams, and perhaps to an even greater degree, Stein was the modernist poetic touchstone for Welch. His 1950 undergraduate thesis on her writing, published by Donald Allen’s Grey Fox Press in 1996 as How I Read Gertrude Stein, is an extraordinary book; it might seem basic now, but there was nothing like it at the time, in terms of someone demonstrating a fundamental grasp of her techniques as a writer. (Frankly, I think most Stein scholars today would benefit from reading it, for most interpretive arguments about her work ignore her techniques entirely.) The influence of Stein and Tender Buttons on “Chicago Poem” is discreet but evident on the level of the line. When, for example, Welch writes of a “Blast of orange like a sunset? Or an orange?” the redirection of attention from the image to the word—the color “orange” suddenly sending him to the name of eponymous fruit rather than further into the visual similarity between the furnace and a sunset—is a lateral move right out of Stein. Too, the lines “In the mills and refineries of its south side Chicago / passes its natural gas in flames” find Welch experimenting with the shifting syntaxes he takes so much delight in in Stein, for, in the Stein-influenced absence of a comma, the phrase “south side Chicago” automatically sends the intelligence one way, before the next line redefines the grammar of the passage and hence the trajectory of the intelligence (“...south side[,] Chicago passes...”). In this respect, among the various allegiances during the period in which he wrote—Black Mountain bowing down to Pound, Beats to Williams—Welch was way ahead of his time, anticipating the New York School’s interest in Stein, let alone Language Poetry’s.

***

Garrett Caples is the author of The Garrett Caples Reader (1999), Complications (2007), Quintessence of the Minor: Symbolist Poetry in English (2010), and Retrievals (2014). He's an editor at City Lights Books, where he curates the Spotlight poetry series and has worked on such books as Tau by Philip Lamantia/Journey to the End by John Hoffman (Pocket Poets #59) and When I Was a Poet by David Meltzer (Pocket Poets #60). He's also a contributing writer to the San Francisco Bay Guardian and co-editor of the Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia (2013). He lives in Oakland.

Garrett Caples is the author of Lovers of Today (2021), Power Ballads (2016), Retrievals (2014), Quintessence...

Read Full Biography