Postscript: Dear Beale Street, Dear Talking Book

In summer of 2018, when I wrote about James Baldwin’s lifelong grappling with all forms of suicide, I scoured every piece of evidence on record, every suicidal testimony I could gather from his art and lived experience in a cavalcade that would pierce the sheen of his celebrity, literary success, and glamorized life as a public intellectual, with the mood indigo glow of that sheen’s grotesque trappings. It was daunting but I didn’t want to leave anything out. I wanted to unravel and undo what seemed like an erasure of his psychic turmoils in the service of where he fits into the American myth that upward mobility is the only solace one would need after generations of trauma, as if becoming a name and an American brand is not as much cause for panic and remorse as it is for some tentative relief, as if some forms of critical acceptance don’t feel like slow mercy killings to the black spirit which is aiming to overthrow the very institutions patting it on the back almost condescendingly—we’ll let you do your intellectual dance, that’s how harmless it is to our dominance. I wanted to point out that being favored by a crowd does not always equate to feeling loved and safe, that acclaim should not mask authentic comprehension in our legacy-making, that what really happens to a man like James Baldwin in daily life is as important as how he happens to us like an awakening. How did we reciprocate, what did we awaken in him? And if part of what we awakened was his contemplation of taking his own life, maybe our passive applause isn’t all that heraldic.

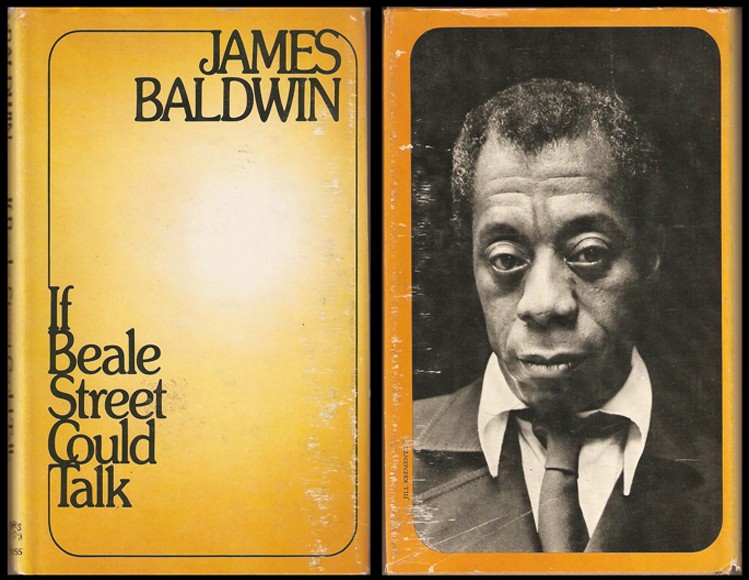

It was necessary to be hyper-meticulous to point out how real this theme of suicide was in Jimmy’s life, but in anticipation of the film adaptation of his If Beale Street Could Talk, I omitted one episode in the procession of suicidal events running through his life and work that I had originally intend to include. It was a tentative muting, but I wanted the newly imagined Beale Street to bleed new blood into the collective memory, so I refrained from discussing the suicide of Frank, the protagonist’s father, and what it indicates of the forgiving love Baldwin harbored for his fathers. Frank in the book and Frank in the movie are introduced in the same way—he’s a jovial and charismatic yet melancholic drunk who works the shipping docks. He and Fonny, his sculptor son who is in jail serving time because of a disgruntled racist cop’s fabrication of evidence for a rape he didn’t commit, share a bond as the only truly free spirits in their family of holy rollers, the only redeemed in a family of sanctimonious redeemers. Frank’s wife is obsessed with the gospel and their two daughters are uppity, over-righteous near replicas of her, so that when the news is delivered to this divided family that the love of Fonny’s life, Tish, is pregnant, it’s only Frank who possesses the spiritual courage and grace to celebrate. The mother throws a tantrum for Jesus and tries to curse the embryo, until Frank slaps her and she leaves feebly with her two haughty daughters, while the fathers, Frank and Tish’s father Joseph, go for a drink. The men will need to make plans to cover Fonny’s legal costs and get him released, and they conspire to steal goods from the docks and sell them uptown in Harlem to make the extra money. It’s devastating to watch these two men anchored to hustles their souls have transcended, two beautiful, talented black men being forced into petty theft by their racist pathologically capitalist country, but it has come to this and at least they’re a team working together to save their family from the well-known mire of false imprisonment. What the film excises is the consequence of the fathers’ filial efforts. Frank is caught by his boss at the docks and fired from his legit job there. He then learns that his son Fonny’s case seems doomed because the woman he’s been falsely accused of raping has gone hysterical and will not change the testimony the DA has counterfeited for her. So, we’re fucked, Frank says. After an outburst that ends with him sobbing with his head in his hands, Frank disappears. He’s found in the woods in his car with the motor running, a suicide. The book ends with this news, the news that Fonny has been beaten up in jail but is still beautiful, his spirit still soaring, and then in a kind of instantaneous reverie of unknotting, the child is born, crying, like it means to wake the dead. The novel ends there.

In the film we get an anesthetized sense of closure, a softer landing. Fonny has taken a plea deal, and Tish and their growing son visit him in prison with snacks—and it’s almost a happy ending, though stilted and a bit too seamless. Too many energies disappear to make way for the valence of a happy family under siege. Beale Street is a gorgeous film, visually, and the story as Baldwin told it is mostly honored, and when I read the book I remember wishing for a sequel because it left this barren sense that all of the characters were doomed, but upon reflection, the strength of the agonies that Baldwin lays bare is that totalizing feeling, all of their power rests in how they transmute that sense of being marked by fate by facing it and using it to wake the dead, not in the denial of it—the treachery they face does not become invisible. The book grabs us by our broken hearts as we are forced to make peace with Frank’s need to extract himself from this reality, and at the same time forced to know that Fonny will learn that his son was born and his father died at nearly the same time, we are forced to face the reality of rebirth, and for me, this end to the story becomes a source of deep solace. It lets us witness the indomitable black spirit, its fertility and endless returning, how one breaking makes way for another entering with tender vengeance. The book’s culmination is brimming with the unwavering realism that makes Baldwin’s work so healing and so devastating—it is the kind of devastation that transforms. The film’s ending, by comparison, offers the spoils that Hollywood would like us to accept as copacetic, a cycle of dysfunction just bearable enough to pantomime an actual American life, a cycle that is never broken because it is never allowed to break. Frank has, no movie for this scene (as Baldwin himself once put it in reference to another black father who was stilted on screen). The dead are never raised, the cries ebb before they get that urgent.

Frank’s suicide is why Beale Street can talk, he haunts it with his knowing, he is the ghost of the future that gives this history its form. He is also, as every suicide that shows up in Baldwin’s writing, an exorcising of the writer’s personal demons. Baldwin’s fathers disappear into madness and anonymity. Both his birth father and the father who raised him come to the kind of ambiguous ends which populate even the most well-adjusted psyche with phantoms and fantasies of eternal return. I don’t know many people with absentee or difficult fathers who don’t find ways to turn those fathers into heroes in our hearts. This turning, this paternal sonnet in the sense of psychic belonging, is a matter of survival, and the forgiveness of both man and circumstance that survival mandates. And as an almost pathological cycle of confession and restraint, forgiveness reinvents itself in other areas of a person’s life and forces one to slay its source again and again, in order to revive it, because what is really at play is a transfigured guilt that no child of a missing father can shed without this theatre of reenactments. Frank dies for Fonny, Fonny will therefore learn the news and feel in some way responsible and he will carve that duty-bound, sometimes-exuberant sorrow into every part of his life and art from then on, so much so that he will work harder to make that art and that life reverent and beautiful, in spite of every pang of resentment and rebellion—this is the biological obedience a father’s ever-present ghost demands. Frank’s death is not sacrifice, it is sacrament, the ritual that situates Beale Street in the autobiographical and teaches us another of Baldwin’s perspectives about his connectedness to his fathers and another of his truths about what he feels he owes to them, what he feels he has been endowed with through their complex and deflected disappearances and devotions. It is also the ritual that makes the chaos and quarreling throughout Beale Street’s plot make sense as what lays the ground for new life paths, new inevitabilities, new dimensions of willfulness. Frank makes the story real when everyone in it is behaving like some mythic hero or villain who passes every test, Frank’s action points out that this is not myth, not every archetype can be contained and rationalized, and that for the characters to learn something and evolve past their petty bickering and worrying, something has got to give, someone must truly and authentically come undone and create space for the new knowing they all desperately need—not everyone in this story can just behave and wait and live on the limbo of hope, that would be a more abysmal tragedy than one brave man’s hopelessly deliberate crossing over.

Beale Street without Frank’s suicide is almost ashamed of itself, it is mumbling, not speaking up. As the pernicious suicidal tendency, and how it activates Baldwin's life-force, in many ways is mostly left out of our understanding of James Baldwin the man, so too is that leaning repudiated in our mainstream depiction of his fictional narratives. The film is tacitly ashamed of its father, of its tragic flaw, of its author who had to face death in every story he told, as he had faced it in his own life. I might be biased because my own father died three days before my sister was born; I’ve witnessed firsthand the kind of resurrection-energy Frank represents, and the kind Baldwin experienced himself when his father died a few hours before his mother gave birth to their last child. The reckless and robust force that always entreats us to watch the dead come back to life is where our stories derive heroic narrators like James Baldwin, condemned to the beauty of bearing eternal witness and forgiving what he sees, condemned to understanding that life for life’s sake isn’t always enough for a black man under siege, that we must work to make life worth living and that men like Frank sometimes go down in that struggle, and are no less courageous or real for it—these same men rise up again, stronger in the brutal power of heirs like James Baldwin. While it’s nice to watch a Black American love story where everyone makes it out alive, it’s a lie. Our love often kills itself to wake the dead, our love lives forever in the risk and threat of violence here, in this country, a violence that has severed black families for generations. Our fathers are in love with life and also murderous and suicidal—they would die for us and have. I wonder if being forced to face Frank’s suicide on screen might have made us leave the film the way we leave the book, unsettled, in love with and forgiving everyone from every Beale Street, and full of things to avenge.

Harmony Holiday (she/her) is a writer, dancer, archivist, filmmaker. and the author of five collections...

Read Full Biography