My Native Language Is Noise

Whenever poet Kim Hyesoon is asked whether her poetry represents her country — a question that is rarely asked of a poet whose work is perceived to be rooted in the Western canon — she never fails to answer that her poetry comes from the Republic of Kim Hyesoon.

Why does Language Poetry soothe me? Because this is what I know: languages exceed our conception of them. They are more than complex forms of cultural activity, more than the material of poem-making, and more than their communicable and informational functions. They won’t be reduced to all the historical, political, economic, aesthetic, and quotidian dramas they animate. Languages live on the continua of silence and noise, blank space and marks, sighted sound and vibrational text.

Currently, I’m working out a poetics of languages as non-symbolic realms of perception, knowing, and communication, by reconstructing my relationship to the languages my parents didn't use with me while using them around me. I’m thinking about making experimental translations of my mother's Philippine language that I neither read nor speak. I'm thinking of transcribing my affective response to the sounds of people speaking. I don't know that I'm planning to write sound poetry (although my project is called AMBIENT MOM) but I’ve been composing while listening to and watching YouTube videos of conversational Pangasinan, which is my mother’s language.

I’ve been reading about cry melodies. Recent research (covered by The New York Times and published in open-source journals) on the prosodic, melodic structures of babies’ cries suggests that people absorb the prosody of a particular language (i.e., French vs. German) while in the womb. While this research analyzes the pitch patterns of babies' cries, jazz pianist Craig Taborn says that kind of rationalizing misses all the information one can get from sound. In the realm of improvisation, it takes "diligence" to enter the field of noise and, while employing all of the training of one's ear, to merely be a co-presence. “Noise is an asymbolic space,” Taborn says. “In my own work, I try to leave some noise.” This makes me imagine building a practice of allowing the languages my parents didn't use with me (while using them around me) to remain (communicative) noise. I’ve already decided against formally learning my family’s languages in order to translate them and instead opt to delve into the ways I somatically know them.

I grew up in 1970s Baltimore hearing two languages, Tagalog and Pangasinan, explicitly not spoken to me. One of the regional languages officially recognized by the Philippine government, Pangasinan is the language of my mother, but not of my father, who grew up primarily speaking Tagalog. My parents spoke a mix of Tagalog and English with one another. My mother spoke Pangasinan with her mother, who lived with us while I was growing up, and on the phone to her siblings. I also heard Pangasinan on yearly visits to my uncles’ and aunts’ three-story house on Manila Avenue in Jersey City, NJ.

In each instance, family members addressed me exclusively in English, and one another in either Tagalog or Pangasinan. I’m the first in my extended family to be born in the United States, and for the first six or seven years of my life, I was the only person kept monolingual in my household and extended family. In his infancy, my younger brother, my only sibling, had his own idiosyncratic language (i.e., “gibberish”), which, out of all of us, my grandmother understood best. He started speaking what I understood to be English a year or two later than expected.

The lingua franca of domesticity was marked as “foreign” for me. I was an American child among Filipino adults with secrets and burdens I trained myself to receive in the hope of understanding but I also didn’t expect any revelation to come down from the heavens delivered to me in plain speech. My persistent scrying into the aural and embodied textures of Tagalog and Pangasinan in domestic spaces was very much of a piece with an upbringing in devotional, repressive Filipino Catholicism. Mysteries can be addictive because they are so very frustrating.

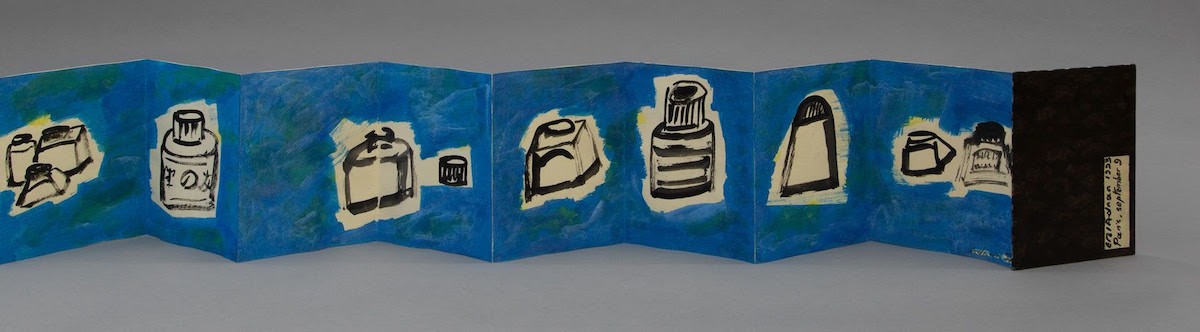

Etel Adnan Untitled (Paris) 1993 ink and water color on paper 8 x 121 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts, NY.

The mystery of my monolingualism is, in fact, not a mystery at all. Assimilation into dominant languages is a common strategy of the immigrant and the colonized. A remnant of U.S. colonialism, English is one of two state languages in the Philippines. The other is Filipino, a metropolitan variant of Tagalog. But the Philippines is a place where between 120 to 187 languages are spoken. Additionally, vibrant code-switching languages, featuring a Filipino language and English, are spoken in the capital of Manila, among overseas communities, among queer Filipinos everywhere, and in popular media.

I was not raised on Filipino-language television, films, or popular music. My immediate family did not regularly visit either of my parents’ home provinces in the Philippines. My Pangasinan and Tagalog childhood took place largely in households and cars, and not in stores, on the street, in schools, or among strangers. English was not the language for expressing opinions or needs, affective or practical. But neither my brother nor I had to be exiled from any room where opinions and needs were being expressed in a language we were not supposed to understand. I developed an ear for emotional prosody: variations in tone, pitch, volume, speed, and pauses. I became sensitized to proprioception, or the language of body positioning, gaze, gesture, muscular tension, and facial expression. The phatic patterns of vocal tics and flourishes came to me undifferentiated from word phonemes. I listened for honorifics that mirrored and performed a place in hierarchies. I wanted to catch someone forgetting to use one and then course-correcting. I wondered because I had no idea how one would learn to use an honorific in a way that did not seem like an extra limb.

The openly unstable and half-imagined sense-making of languages has created space and autonomy in my perception, interpretation, and affiliations. Into adulthood, I feel at home among people speaking any language I do not. While excluded in multiple ways from meaning-making, I am excused from obligations to pay attention and participate in any normative, culturally-specific ways. When people speak their own language around you, they neither police what they want you to hear nor enlist you into their particular rationalities. You are both apart from and a part of what’s going on. It’s an experience of intimate abstraction to be included through forms of sonic and somatic environments, the non-lexical elements of togetherness.

I wonder: Do we belong to one another when languages are at work and at play without interpretation, translation, or understanding? Do the languages we use belong to us? Do I have voided claims over languages I cannot make use of? Can I claim languages I do not speak through my intimacy with their emotional prosodies? Must I speak them to anyone other than myself?

The defamiliarization and estrangement of language is the softening of a property relation between reader and word. It is a hint of recognition, an opening toward animistic co-recognition. It is a sense of the autonomy of words, rather than their exchange value. It is to depart from the practice of claiming a past and future steeped in the dramas of respectability and melancholia and instead to forge living and literary practices in which the noise might be communicable, recognized (gnosis), encounterable, and translatable.

Cover image credit: Hilma af Klint Group I, Primordial Chaos, No. 16 (Grupp 1, Urkaos, nr 16), 1906-1907 from The WU/Rose Series (Serie WU/Rosen) Oil on canvas, 53 x 37 cm. The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm. Photo: Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Kimberly Alidio (she/they) is the author of Teeter (Nightboat Books, 2023), why letter ellipses (selva...

Read Full Biography