A Pair of Andys

Looking at Andy Warhol through Andrew Marvell's eyes, and vice versa.

Introduction

See how he nak’d and fierce does stand,

Cuffing the thunder with one hand,

While with the other he does lock,

And grapple, with the stubborn rock:

From which he with each wave rebounds,

Torn into flames, and ragg’d with wounds,

And all he says, a lover dressed

In his own blood does relish best.This is the only banneret

That ever Love created yet:

Who though, by the malignant stars,

Forcèd to live in storms and wars,

Yet dying leaves a perfume here,

And music within every ear:

And he in story only rules,

In a field sable a lover gules.

These closing stanzas of Andrew Marvell’s “The Unfortunate Lover” are among the most beautiful and chilling in English poetry. As the anonymous lover thrashes through his furious death and transformation into a gorgeous, grotesque work of art (In a field sable a lover gules might be paraphrased as “On a black field, a red lover”), Marvell too transforms his perception, from empathy and engagement into something like connoisseurship. I’ve come to think of “The Unfortunate Lover,” alongside a handful of other Marvell poems, as recasting in elegantly rhymed and discordant words Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” paintings: those astonishing orange, pink, blue, red, and lavender canvases of suicides, car crashes, race riots, and electric chairs. In a field sable a lover gules even suggests a fancy alternative designation for, say, Deaths on Red (1962) or Red Disaster (1963), and Marvell’s invocations of Death (“Yet dying leaves a perfume here”) and Disaster (“malignant stars”) suggest the series title itself.

Let me try to explain. My senior year in college I sent a letter to Andy Warhol care of the Factory, then at 33 Union Square, NYC. I was trolling for a job. I mentioned my friendship (really no more than an awed, clumsy acquaintance) with an aging Superstar, Ed Hood—the notorious ’my’ of My Hustler,” as the Boston College English professor who introduced us quipped, referring to the 1965 Warhol film, late one night upstairs at the Casablanca in Harvard Square.

A Harvard student some 20-plus years into the doctoral program in literature, Ed was still writing a dissertation on love in Shakespeare. He may also have been the smartest person I had met up to this point, and he certainly proved the seediest. Another evening I found him at the Casablanca seated between a teenage boy and an older man dressed for the office in a brown suit and tie. “Robert,” he called to me, enunciating in the clipped, Alabama-aristocrat inflections he favored when drunk, “I want you to meet my date . . . and his parole officer.”

This turned out to be accurate, and as we chatted, the “date” played with a long screwdriver, practicing how to slip it out and back into the sleeve of his motorcycle jacket without using his hands. After hours, back at his tiny apartment behind the Casablanca, Ed would recite John Crowe Ransom’s poem “Janet Waking” as he drank red wine from a milk glass and pulled down books and manuscripts from his shelves. For one of his birthday parties, he stood by the door in his Brooks Brothers seersucker robe, a variation on the one he wears in My Hustler, snapping a tiny leather whip: “I see you’ve come for a taste of the cat!”

Ed Hood knew everyone. Through him I encountered most of the Cambridge Warhol crowd that would people Edie (Jean Stein and George Plimpton’s oral history of Edie Sedgwick) along with that crowd’s assorted New York visitors: Ed Hennessy, Chuck Wein, John Hallowell, Gerard Malanga, Lou Reed, Rene Ricard, Donald Lyons, Patrick Fleming, Dorothy Dean, Jonathan Richman, and Andy Paley. Ed appears in Edie both under his own name and disguised as Cloke Dosset:

I remember a sophomore, a very nice Porcellian boy—they seemed to be the most fragile—whom Cloke saw across the room at the Casablanca and apparently liked. He got his attention just by focusing on him, and then he walked across the room very slowly, snapping his fingers, click, click, click, and finally he got right up to him, and the boy fainted! He was on the crew and a big jock . . . .

— Ed Hennessy, in Edie: An American Biography

from Stylus |

Years earlier Ed had occupied an editorial position at Shenandoah, and he gave me some correspondence sent to him at the journal from Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, and Marshall McLuhan for publication in Stylus, the Boston College undergraduate literary magazine I edited with a few friends. Each letter sounded exactly as you’d expect—Pound cranky (“if HOOD has heard of agrarians / for GOD’Z ache keep him at it”); Moore gracious if dazed (“I thank you for your hospitable letter of April 21. . . . That you liked my translation of La Fontaine, and liked my prose, encourages me”); McLuhan forceful and enigmatic (“Apropos of relation of Counterblasts to W. Lewis, let me point out the irony”). Everyone assumed we wrote the letters ourselves, and invented Hood. Ed also interviewed the novelist Rosie Blake, crafting her answers as well as his questions, and then arranged for a Gerard Malanga photograph of Blake. For me and my college friends, Andy Warhol was a way of looking at the world, if not necessarily at our own actual lives.

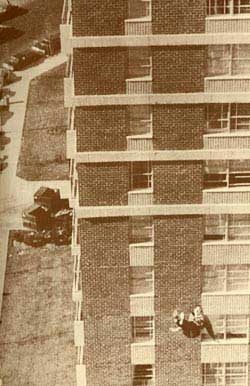

Editing Stylus allowed us a sort of local theater for our homage to Warhol. One issue, a lavish, smash-the-school-budget celebration of suicide and show biz, featured a full-color reproduction of the lyric sheet to “There’s No Business Like Show Business” on the front cover, and on the back a black-and-white photograph of a man caught in midjump from the top of an apartment building. We purchased the image from Wide World Photos for $25, as I recall, and inside Stylus we mixed stars (movie, rock, literary, faculty, student) and deadpan lists of suicides, probable suicides, even likely future suicides.

from Stylus |

The key reference here, I suppose, was Warhol’s Suicide (1962), an early painting that also froze in midair a man on his way down to his death; but the cover swept up as well the various Marilyn, Liz, and Jackie silk-screens. Our catchphrase for the so-called design team behind Stylus, Snell Enterprises, echoed the faux prole aura of the Factory. All the Factory films were officially out of circulation, though I would soon see Chelsea Girls (1966) and Vinyl (1965) after Ondine, another Superstar, started touring campuses with them.

Among my Boston College friends, Warhol radiated a sly, sinister hipness, a tangent to the dread, doom, and spectacle of our Catholic childhoods. The holy relics of that hipness included the Velvet Underground, stills from those legendary “lost” movies, and the “Death and Disaster” paintings. Starting with this trinity, the art that most attracted us, from Beckett, Barthelme, Lowell, and Nabokov to film noir and the Kinks, was death-haunted and smart, and mixed emotional ferocity and formal beauty. This art was both ascetic and hedonistic, at wit’s end, funny, and not really ironic. That is, the obvious ironies of all these artists are so thoroughly insinuated inside extremes of feeling and behavior that the jokes only intensify the dismay.

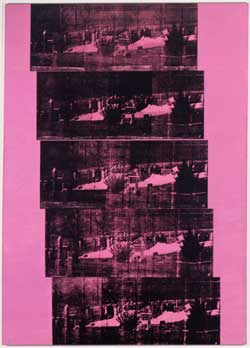

Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” paintings dig into perhaps the most grisly subject matter in the history of American art. Originally titling the series “Death in America,” he worked on it roughly from the summer of 1962 through 1967, most intensively during 1963 and 1964. These paintings coincided with Warhol’s evocations of Marilyn Monroe (which he began soon after her death in August 1962), of Elizabeth Taylor (first planned during her 1960 Cleopatra illness), and of Jackie Kennedy in Dallas. Although the earliest canonical “Death and Disaster” painting is likely the handpainted New York Mirror front page 129 Die in Jet) (1962), Warhol found his template in Suicide (also 1962): news photographs silk-screened onto large canvases against a single background color that appeared to rinse the spectral images in a wash of menacing grays or vivid hues.

As he moved among suicides, tragic Hollywood and historical actresses, automobile wrecks, racial violence, criminals, and electric chairs, Warhol—more than any 1960s creator other than Bob Dylan—gave aesthetic form to his own and his culture’s immediate, ongoing experience. The effect, like Dylan’s, was slippery, and the “Death and Disaster” paintings could (and have been) read in sometimes overlapping, often contradictory ways. Spiritually—as the redemption of the most painful human experiences by art, and as an iconography of hell. Politically—as a corrosive probing of the public fever-dreams of American life. And, finally, as—what’s the best phrase?—“mindless pleasures,” to lift Thomas Pynchon’s jettisoned title for Gravity’s Rainbow: the flashy colors make the images look so dumb and dunced-out, as if all that matters is whether, say, Mustard Race Riot (1963) or Deaths on Turquoise (1963) matches your new rug. Brutal, gorgeous, the “Death and Disaster” paintings appall, titillate, and move 40-plus years down the line. I know of nothing exactly like them.

* * *

Andy Warhol Gangster Funeral, 1963. Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. 2006 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

Andy Warhol didn’t answer my letter, and instead I went to graduate school for English literature. At orientation the chair handed out a roster of current doctoral candidates, arranged by seniority. Ed Hood’s name headed the list—a 23-G, I think—but I rarely ran into him around the department. According to legend, anyway, Ed was forbidden to enter Harvard Yard except for registration and meetings with his advisor, William Alfred. Still, Warhol hovered over my literature classes—especially when, during my initial semester at Harvard, Stephen Koch published his book Stargazer: Andy Warhol’s World and His Films, and gave me a language for the world that all along my Stylus friends and I had been looking at through Warhol.

Except for Richard Poirier’s The Performing Self, or William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity, I would never be so galvanized by a critical book. Koch introduced Warhol as a dandy, citing Sartre’s famous definition, which I was reading for the first time: “The character of the dandy’s beauty consists above all in the cold appearance which comes from the unshakeable resolution not to be moved; one might say the latent fire which makes itself felt, and which might, but does not wish to, shine forth.”

Warhol, as Koch tracked him, was “the solution to a problem.” If this problem, broadly limned, was everyday life and its discontents, then the solution was a fierce, chintzy anesthetization: “He is an artist whose glamour is rooted in despair, meditating on the flesh, the murderous passage of time, the obliteration of the self, the unworkability of ordinary living. As against them, he proposes the momentary glow of a presence, an image—anyone’s, if only they can leap out of the fade-out of inexistence into the presence of the star.”

For his paintings and films, in his art and his life, Warhol (Koch suggested) replaced “the dimension of Personhood in himself with an exaggerated dimension of Presence.” His Warhol inverted Wordsworth: “Strong emotion recollected in tranquility had to become strong reality aestheticized in immediacy.” The “Warholvian stare,” as Koch styled his aesthetic gaze, “is a major metaphor for art and life in our time,” and “Warhol’s entire career can be understood as an attempt to redeem that despair without belying it.”

Koch offered up Warhol as an artist who wouldn’t flinch—at least until his shooting by Valerie Solanas in 1968. As Koch summed him up: “At the core of the passivity, the chic, the affectlessness, at the center of the phenomenally interesting thing he did with the incapacity to love or connect or believe, there was something crucial and dangerous: a very profound doubt about the value of life itself.”

A very profound doubt about the value of life itself. This was a chill beyond most poetry—though I would later find hints of it in some of Browning’s poems, such as “The Laboratory” or “My Last Duchess.” And that first year in graduate school, during a class on the Metaphysicals with the Shakespeare editor G. B. Evans, I found it everywhere in Andrew Marvell, particularly in his poems on painting and art.

Let me again try to explain. In his writing Marvell is at least as much an aesthete as Warhol. Perhaps the most common situation in his poetry is a debate between two or more articulated styles of living. Occasionally, this is carried on with some directness. In “A Dialogue, between the Resolved Soul and Created Pleasure,” or “A Dialogue between the Soul and Body,” or “The Mower against Gardens,” for instance, the subjects and general forms of the arguments are suggested in the titles. “The Garden,” “On a Drop of Dew,” “Upon the Hill and Grove at Bilbrough,” and “Upon Appleton House,” from very different traditions and perspectives, argue aspects of the active and meditative ways of life. “A Dialogue between Thyrsis and Dorinda,” “Clorinda and Damon,” and “Ametas and Thestylis Making Hay-ropes” all debate some elements of pastoral—secular versus Christian pastoral, “civilized” versus “natural” sexual love.

At other times the debate is implicit in the complementary and contradictory languages of a poem. In “Damon the Mower,” “The Mower to the Glowworm,” and “The Mower’s Song,” Marvell introduces romantic love into a pastoral environment. “The Coronet” examines personal sincerity in the form of sacred and profane poetry. And “Young Love,” “The Picture of Little T.C. in a Prospect of Flowers,” “The Garden,” “To His Coy Mistress,” and “Ametas and Thestylis Making Hay-ropes” locate the carpe diem, carpe florem trope in an astonishing range of dramatic contexts.

There is something misleading about the application of a metaphor of debate to these poems, and this is the point where the notion of Marvell as an aesthete starts to simmer. Both generically and in common parlance, “debate” implies a conclusion and a victor, but neither of these exists in Marvell’s poetry. His writing eludes thematic analysis, even of a refined sort. The poems are turned into statements only by doing violence to the range and quality of their tones.

Yet virtually all his lyrics, and some of his satires, exhibit an interest in ideas—in epistemology, types of poetry, style and the history of styles—that, I think, can be talked about, provided one recognizes that his interest is in the shape of ideas, their formal properties and the processes of imagining them, and does not extend to judgments about truth or belief. His poems are explorations of aesthetic and metaphysical problems, studies in tentativeness and complexity. Often they are as “open-ended” as the essays of Montaigne, and Marvell resists general ideas and conclusions as successfully as any artist, even Flaubert or Proust or Beckett. The shape of an idea, the history of its contexts, and its dramatic, structural, and literary possibilities are its significance.

This is to say that, despite the frequency of debate in his poetry, Marvell very rarely, if at all, makes any special claims about the superiority of a particular style. Approached in this way, his poems are most often appreciations of the limitations and failures of style, of the inability of a style to control the problems that it has, presumably, been invented to solve. Styles fail in Marvell’s poems for combinations of reasons: a style might no longer be supported by its traditions; those traditions may have become decadent, or in some other fashion outmoded and devitalized; a style may be asked to consider situations outside of and inconsistent with its traditions. Or failure might be apprehended as the necessary consequence of having a style, any style.

Andy Warhol Ambulance Disaster, 1963-64. Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh 2006 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

While both of the poems that I wish to discuss now participate in these and related failures of style, they also concern themselves with a pair of stylistic solutions familiar to Warhol: the stylization and aestheticization of human behavior.

The poems are “The Unfortunate Lover” and “The Gallery.” Both address obsessed, obsessive actions at the edges of violence, and advance, after the fashion of the “Death and Disaster” paintings, riddles of trauma, performance, and art.

“The Unfortunate Lover” traffics in frustration and the compulsion to fail. The eponymous hero of the piece is rare in Marvell’s poetry in that he speaks at the top of his voice, and Marvell has written into the stanzas a second protagonist who operates as a reader and critic of the unfortunate lover’s conduct. The poem, not unconventionally, imagines life and love as a sea journey, and the lover’s birth by Caesarean section becomes a shipwreck:

’Twas in a shipwreck, when the seas Ruled, and the winds did what they please,

That my poor lover floating lay,

And, ere brought forth, was cast away:

Till at the last the master-wave

Upon the rock his mother drave;

And there she split against the stone,

In a Caesarean sectión

The image is as imprecise as it is extravagant and grotesque—the ship must stand for both mother and child. But the situation is clear: the lover is rendered as having been doomed, or “unfortunate,” even before he was born. The stanza plays against the notion of the happy shipwreck (as in Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors or The Tempest). This lover was palpably born into his element but, as these next lines suggest, his survival can hardly be counted an advantage:

The sea him lent those bitter tears

Which at his eyes he always wears;

And from the winds the sighs he bore,

Which through his surging breast do roar.

No day he saw but that which breaks

Through frighted clouds in fork’d streaks,

While round the rattling thunder hurled,

As at the funeral of the world.

A storm becomes the principal image for the lover’s emotional life. Deftly Marvell summons Saint John’s Apocalypse and compares the lover’s birth to the end or “funeral of the world.” The unfortunate lover’s qualities are also Petrarchan—his “bitter tears,” his “sighs”—as is the device of linking them to the physical environment, to the rain, the winds, and the thunder. But unlike Petrarch, Marvell does not really offer these as comparisons; he literalizes them, undermining their traditional status as metaphors, and presents them as attributes contributed (“lent”) directly by the circumstances of his birth. The stanza becomes what might be called a “reading lesson” in the appreciation of the preceding one, as the speaker brings to it some of the critical and analytical skills that, normally, readers are asked to supply. He examines and explicates the language of the prior stanza, showing in what ways it is appropriate for the unfortunate lover, rendering explicit what was only suggested in the “storm” and “shipwreck” images.

The relationship between the ensuing two stanzas is much the same. These concern the lover’s upbringing and education:

While Nature to his birth presents

This masque of quarrelling elements,

A numerous fleet of cormorants black,

That sailed insulting o’er the wrack,

Received into their cruel care

Th’ unfortunate and abject heir:

Guardians most fit to entertain

The orphan of the hurricane.

They fed him up with hopes and air,

Which soon digested to despair,

And as one cormorant fed him, still

Another on his heart did bill,

Thus while they famish him, and feast,

He both consum’d, and increased:

And languish’d with doubtful breath,

The amphib’um of life and death.

Marvell sketches an ironic social scene. The unfortunate lover is imagined as an “orphan” and “heir”: the cormorants are his “guardians,” and he has been entrusted to their “care.” Yet the nagging adjectives—“insulting,” “cruel,” “unfortunate,” “abject”—qualify the nouns almost to the point of negating them, and deflect the improvised domestic setting.

Qualification and negation also occupy the following stanza, which is presented as another “reading lesson”—this time to demonstrate why the cormorants are “most fit” to raise the unfortunate lover. The passage turns on some sly, virtually sophistic etymological associations. “Cormorant” (a large, black sea-bird, from corvus marinus) often was linked to “cor-vorax,” meaning gluttonous or voracious—an appropriate misassociation in light of the bird’s rapaciousness, which carries over into the word “cormorous” (“insatiable as a cormorant”). Here Marvell presents the lover as the cormorants’ plaything. The birds are not voracious (or, alternatively, not kind) enough to finish him off, preferring to keep him alive so they might watch him suffer. The verbs come in pairs that alternate sustenance and consumption—the birds feed “him up with hopes and air, / Which soon digested to despair”; one cormorant nourishes him as another pecks at his heart (cors, in Latin, still another dubious echo); they both “famish him” and “feast” on him, and he is at once “consum’d” and “increased.” This chronicle of his tormented youth concludes with one of Marvell’s most memorable couplets: “And languish’d with doubtful breath, / The amphib’um of life and death.”

The next stanza presumably depicts the unfortunate lover’s romantic and sexual life:

And now, when angry heaven would

Behold a spectacle of blood,

Fortune and he are called to play

At sharp before it all the day:

And tyrant Love his breast does ply

With all his winged artillery,

Whilst he, betwixt the flames and waves,

Like Ajax, the mad tempest braves.

This “spectacle of blood” arises out of metaphorical figments like “love’s arrows” that once again Marvell literalizes. The lover is fixated, violent, perpetually at war, and self-defeating. He is first a swordsman—“Fortune and he are called to play / At sharp . . . ,” and “tyrant Love his breast does ply / With all his winged artillery.” Then he is compared to Ajax, the reference probably being to Sophocles’s Ajax, and denoting Ajax’s disappointment upon not receiving the armor of Achilles. If so, the link is apt, as the image of mad Ajax hacking away at a flock of sheep, convinced that they are the Atrides, summons the violence, delirium, and rage that propels the unfortunate lover.

By now it should be obvious that the language of this poem is prodigal, fantastic, and intermittently ridiculous. Marvell stretches his linguistic resources past the breaking point and leaves them lying there in pieces, as if taunting us to pick them up or start laughing. Yet there are few or no parodic elements in “The Unfortunate Lover.” Marvell disposes a study of obsession, a style of loving pushed past the limits, and the language affirms and complements this. What is most remarkable about the lover’s frustration is that he enjoys it, that he regards his pain with “relish”:

See how he nak’d and fierce does stand,

Cuffing the thunder with one hand,

While with the other he does lock,

And grapple, with the stubborn rock:

From which he with each wave rebounds,

Torn into flames, and ragg’d with wounds,

And all he says, a lover dressed

In his own blood does relish best.

Here the lover apprehends himself as a performer—he is not so much consumed by love as by the artistic and exhibitionistic terms of his performance. Those terms, the quixotic emotionalism, the outlandish gestures, the rage, the violence, amount to a denial of love, unless one posits a love motivated only by anger. Notably, no women or men appear in the poem, and we never witness the lover as a lover, failed or otherwise. In regard to the title, the emphasis clearly falls upon the adjective rather than the noun. It is his status as an “unfortunate” that the lover flaunts in his theatricality, and it is the self-staging of an “unfortunate” that he proposes to pass off as love.

One fascinating source of the wild language of “The Unfortunate Lover” resides in the pictorial traditions upon which the poem draws. Almost everyone who has edited Marvell points to the “emblematic” nature of this writing. Virtually all of the major images can be traced to emblem books, particularly to Otto van Veen’s Amorum Emblemata (1608), Hermann Hugo’s Pia Desideria (1624), and Francis Quarles’s Emblems (1635).

But Marvell does not approach emblems in a manner we associate with 17th-century poetry. His handling of the emblematic tradition transposes the practices of, say, George Herbert. The critic Rosalie L. Colie addresses this reversal with perspicuity and precision: “In ’The Unfortunate Lover,’ Marvell points to the origins of emblems by reversing the normal emblematic procedure, which was to make extravagant pictures from hyperbolical metaphors. In this poem, he extends the usual range of metaphor and conceit by borrowing from the extravagant and conceited pictorial tradition, itself based on figures of speech. . . . Here he starts from the heightened fantasy of the emblem to take their overstatements literally, as the ’real’ setting of this lover’s life.”

This practice parallels a feature of Marvell’s style I glanced at earlier—his surprising and mysterious literalization of conventional metaphors. Such gestures at once intensify and level the charged materials that passed from speech into the emblems and then back into his poem, rather like Warhol’s mechanical silk-screening of news photographs and his decorator colors.

But what if, instead of the unfortunate lover, we focus on the speaker who is attempting to render him? This speaker’s characteristic way of proceeding is to distance the violent and disturbing elements of the lover’s behavior and nudge them toward art. He is responsible for the “reading lessons” I mentioned above, and he also attempts to domesticate and stylize passages of the poem—by imagining the lover as an “orphan” and the cormorants as his “guardians,” or by turning his encounter with fortune into a romantic duel. The opening lines of the “The Unfortunate Lover” point to the speaker’s self-consciousness:

Alas, how pleasant are their days

With whom the infant Love yet plays!

Sorted by pairs, they still are seen

By fountains cool, and shadows green.

But soon these flames do lose their light,

Like meteors of a summer’s night:

Nor they to that region climb,

To make impression upon time.

“Alas” is the sole word here that could refer to the unfortunate lover. The speaker locates his language among various traditions of love poetry, outlining love poems that have been written and poems that on other occasions he might write. He underscores the traditions his present poem will refute: the unfortunate lover’s days are not “pleasant”; “infant Love” later becomes “tyrant Love” as “plays” turns into “play at sharp”; there are no “pairs” in this poem, only a solitary “unfortunate”; the “fountains cool” are replaced by a “mad tempest” and “flames and waves”; “green” is nowhere to be discovered, as this lover’s colors are black (the cormorants) and red (his blood).

The speaker makes his only direct appearance in the second stanza in a reference to “my poor lover.” The phrase estranges the unfortunate lover’s emotions in at least two ways. First, it calls attention to the fact that we are reading a poem with a speaker who stands between us and the lover, accenting the artifice. Second, the hint of personal possession (“my”) carries the effect, if only momentarily, of turning the lover into an object.

Elsewhere in the poem this speaker introduces his subject in the language of classical tragedy. We are informed that what we are witnessing (“See . . . ”) is somehow inevitable, necessary: “And, ere brought forth, was cast away.” Nature is depicted as an impresario or a producer:

While Nature to his birth presents

This masque of quarrelling elements. . . .

Heaven becomes the audience:

And now, when angry heaven would

Behold a spectacle of blood. . . .

There is a profusion of theatrical vocabulary: “play,” “plays,” and “entertain,” as well as “masque,” “behold,” “spectacle,” and “presents.”

In the last stanza, this speaker completes his pattern and transforms the bloody lover into an art object:

This is the only banneret

That ever love created yet:

Who though, by the malignant stars,

Forc’d to live in storms and wars;

Yet dying leaves a perfume here,

And music within every ear;

And he in story only rules,

In a field sable a lover gules.

The lines mark the speaker’s final adjustment of his cognitive frames. He shifts his attention away from the unfortunate lover to his own acts of perception in a search for alternate ways the lover might be understood or portrayed. His solution is an aesthete’s. He makes sense of, and then redeems, the lover’s hurt, ugliness, and violence by giving aesthetic form to it. He provides a fresh context for the lover to be approached as art, moreover as sweet and dazzling art. He also resolves the problem of his own engagement with his poem’s subject: all that was bothersome, shabby, and troubling about the lover disappears beneath what Stephen Koch, writing of Warhol, calls an “affectless gaze.” That penultimate line, “And he in story only rules,” both epitomizes his process of translating the lover into art, and puns on the Renaissance idea that works of art are beyond the effects of time. His conclusion asserts the unfortunate lover’s superiority over those happy lovers who earlier

. . . do lose their light,

Like meteors of a summer’s night:

Nor can they to that region climb,

To make impression upon time.

The relationship between this speaker and the unfortunate lover is that of connoisseur and icon. This is hardly an uncommon situation in Marvell’s poetry, especially in those pieces usually designated as his love-lyrics. In “The Definition of Love,” the strongest and most precise emotion is the speaker’s pleasure before the elegance, wit, and formal beauty of his own demonstration of why his love is impossible. Another poem of this type is “The Gallery.” This poem is a more obvious instance of ecphrasis (the presentation of visual material in language) than “The Unfortunate Lover,” and once more investigates the practice of ransoming turmoil by means of art in the guise of a poem about an obsessed lover.

The situation of “The Gallery” is reminiscent of Donne’s “Elegies” in the way that it suggests, but does not complete, the form of a dramatic monologue. The poem is a kind of invitation, not to love, but to review some pictures: “Clora, come view my soul, and tell. . . .” Recasting his soul as an art gallery, the speaker describes his collection as “choicer” than “Whitehall’s or Mantua’s” (two contemporary court collections) because his portraits are all of just one person: his love, Clora. She is summoned as if she were also a critic to tell him how well he has “composed” and “contrived it.”

A gallery is a clever device for depicting obsessive love. The poem describes five portraits, each one a stylization of a woman-lover with shifting yet recognizable analogues in Renaissance literature and painting. The first four portraits are unveiled in pairs, each pair occupying two sides of a single canvas. In each pair, an active and cruel lover contrasts with a passive and lovable one.

We first see Clora “painted in the dress / Of an inhuman murderess,” testing her “engines” of torture—that is, her “[b]lack eyes, red lips, and curl’d hair”—on the heart of her poor suitors. But “on the other side” (these are not ordinary “arras-hangings,” as he says, but reversible), she is “drawn / Like to Aurora in the dawn,” and we view her just as she wakes up, stretching “out her milky thighs,” bringing light and life to the “roses” and the “wooing doves.” For the second pair, she emerges as an “enchantress,” utterly self-absorbed in her beauty, raving over her lover’s entrails “with horrid care”; and then she is “[l]ike Venus in her pearly boat,” with props we associate with Venus—halcyons, a rolling wave of ambergris, her perfume.

Perhaps the most devious of the portraits is his last:

But, of these pictures and the rest,

That at the entrance likes me best:

Where the same posture, and the look

Remains, with which I first was took:

A tender shepherdess, whose hair

Hangs loosely playing in the air,

Transplanting flowers from the green hill,

To crown her head, and bosom fill.

Marvell elegantly handles the business of love at first sight. But less obviously he is having some sport with the pretenses of literary pastoral. These lines appear to be making a claim for Clora’s naturalness, setting this portrait against the obvious artificiality of the previous four. Yet the pastoral image on this canvas is no less conventional than any of the others. Naturalness is its convention.

As in “The Unfortunate Lover,” there is only private drama to this affair, and love itself does not figure significantly in the poem. Clora is no more present at the conclusion of the piece than she was at the beginning; the syntax of the first stanza (“Clora, come view . . .”) places her outside of it, turns her into a silent witness, and there she remains. The speaker is promoting himself as an obsessed lover, but his obsession does not involve Clora, or even love. He is obsessed with his paintings, which are the wellspring of his strongest feelings:

These pictures and a thousand more

Of thee my gallery do store

In all the forms thou canst invent

Either to please me, or torment:

For thou alone to people me

Art grown a numerous colony. . . .

His pleasure inheres in contemplating his own skills as a curator. There is nothing she could do to surprise him, as he is always at least one imaginative step, one painting, ahead of her, ever in control of “all the forms” she “canst invent / Either to please me, or torment.” Here the speaker may be calling attention to Clora’s status as a poetic fiction. Or these lines may reflect criticism of Clora: she is all pose, and every aspect of her behavior partakes of role play, and since her poses and roles are familiar ones—at least familiar to him—he can predict the parts she will play for him.

But throughout, there remains the insinuation that Clora is at least as complex and various as the speaker’s visual anthology indicates, and that his gallery of ready-mades is his way of managing her. He objectifies her in art—as the Duke of “My Last Duchess” does, pointing to the portrait of his murdered wife, and still more as Warhol does. The gallery is in a sense this speaker’s Factory, and as Koch writes of Warhol, “A man had transformed himself into a phenomenon; one looked into him and saw—a scene.”

The twin speakers of “The Unfortunate Lover” and “The Gallery”—might we now tag them both Andy?—approach people with the assumptions, interests, and values of an aesthete. Their attitudes can also be dubbed voyeuristic, though their voyeurism is as aesthetic as it is sexual; or here the aesthetic and sexual merge. To paraphrase Koch on Warhol, both withdraw from painful, disturbing situations; they exchange the agency of their personal involvement, even the agency of their own personalities, for “Presence.” They construct contexts where emotions and human actions may be appreciated as objects, as art. Those contexts, which constitute that “Presence,” reside in the way they choose to look at their subjects, that is, in gazing itself (“See . . .”). Consciousness then becomes a theater, an art gallery.

This is in a very real sense a “solution,” for Marvell’s poems as well as Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” paintings. It’s inevitably trickier, however tempting, to pass through the frames into personal matters of style and biography. For the Andrew Marvell who issues from John Aubrey’s Brief Lives sounds at least as spooky as Andy Warhol:

This is in a very real sense a “solution,” for Marvell’s poems as well as Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” paintings. It’s inevitably trickier, however tempting, to pass through the frames into personal matters of style and biography. For the Andrew Marvell who issues from John Aubrey’s Brief Lives sounds at least as spooky as Andy Warhol:

He was of a middling stature, pretty strong set, roundish faced, cherry-cheeked, hazel eye, brown hair. He was in his conversation very modest, and of very few words: and though he loved wine he would never drink hard in company, and was wont to say that, he would not play the good-fellow in any man’s company in whose hands he would not trust his life.

He had not a general acquaintance.

He died in London, 18 august, 1678. Some suspect that he was poisoned by the Jesuits, but I cannot be positive.

* * *

Ed Hood may not have been poisoned by the Jesuits either, but he died almost exactly 300 years later, in the spring of 1978. After speed and alcohol induced something like epilepsy, he checked into McLean psychiatric hospital to dry out. He lost his apartment behind the Casablanca, and I never determined where he moved, though you’d still see him around Harvard Square. He talked about writing his dissertation, and applying for teaching jobs, maybe down south, but you knew it was not going to happen. One rumor was that while experiencing a seizure, Ed fell and cracked his head on a table. The other was that he choked during rough sex with a hustler, who then out of fear or remorse killed himself in the morning.

Poet and scholar Robert Polito was born in Boston, Massachusetts. He earned his PhD from Harvard University and has served as director of Creative Writing at The New School for two decades. Polito served as president of the Poetry Foundation from July 2013 through June 2015.

Polito’s collections of poetry include Hollywood & God (2009) and Doubles (1995). His poetry blends narrative and lyric impulses...