Charles Bukowski, Family Guy

Born into a life shaped by the man—and the myth.

BY Molly Young

Introduction

"What I knew at age 13 about Charles Bukowski was nothing."—Molly Young shares how she came to know Charles Bukowski.

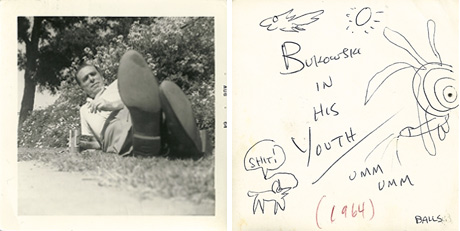

Photo of Charles Bukowski sent to Lafayette Young.

Photo of Charles Bukowski sent to Lafayette Young.1. Flower Rock

For several years I slept inside a storage shed with a collection of Charles Bukowski’s letters called Living on Luck. The house my mother bought in Bolinas sat at the edge of a meadow and offered deer-spotting and blackberry access, but it was too small for a four-person family. A storage shed was erected in the backyard, insulated and outfitted, and given to me as my bedroom. (My younger brother slept in the loft of the real house, my older brother had the living room, and my mother took the one bedroom.)

It was exciting, the shed: my previous room had been a closet with an egg-crate foam bed, and now I was in charge of an outbuilding with its own mulch pile and locking door. The room had a desk, a bed, and a jar of peanut butter in case I got hungry during the night. A bookshelf held a mixture of my mother’s New Age books, books by family friends, and books that had belonged to my grandfather. This last section included some Djuna Barnes, Kenneth Rexroth, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and a bunch of chapbooks with dirty pictures in them.

What I knew at age 13 about my grandfather, Lafayette Young, were the following things: he was an alcoholic, he owned a bookstore, he was gentle, and he died in 1981, five years before my birth. People called him “Lafe,” he ate ice cream, fathered children out of wedlock, lived for a while in Mexico, and, when tanned, could pass for a Mexican. From my mother’s reports I gathered that Lafe was an interesting and depressive person who made life difficult for his family.

There was also the manuscript he wrote, or co-wrote. Where did I find the manuscript? Can’t remember. Possibly in the shed. The folder was avocado-colored and labeled Flower Rock, and it contained a book’s worth of loose typed pages written in alternating sections by Lafe and his wife, my grandmother Bethel Young. The memoir was plain but enchanting. It described a young couple living with their three young boys in southern California in the late 1940s. From Flower Rock I learned what Lafe ate for lunch, when he went to bed, and that he nicknamed his sons Chiqui, Tanto, and Bobi.

What I knew at age 13 about Charles Bukowski was nothing.

2. Living on Luck

I opened Bukowski’s Living on Luck because the doodle on the cover was appealing, and I read it because there was a Young, Lafayette entry in the index. There was also, and more excitingly, a Young, Niki entry one millimeter below it. Niki is my mother, Nicole, and a letter dated May 1970 from Bukowski to Lafe includes the injunction to Stay in there Niki. What was my mother, aged 17, supposed to stay in?

The book includes a handful of letters to Lafe covering a span of two years. Bukowski wrote to him about going mad (“total days fucked away and torn up”), the business (“frankly, most editors look at the writer as some kind of idiot”), praise from admirers (“I say, “yeh.” who cares? I’d just as soon piss on it”), and writing (“I don’t want to sound holy about it; it’s not holy—it’s more like Popeye the Sailor Man. But Popeye knew when to move”). And also about drinking: “Don’t worry about alcoholism; it keeps us from committing suicide.”

This was an odd way to meet a writer, and an odd way to meet a relative. From the book came admiring memories of Lafe; from my mother came tender and hurtful memories. She would mimic his lunges to the fridge for a beer. Her brothers were angrier. They wrote about the bloated face, the dribble of blood from the mouth, the retching.

Said Bukowski: “I hate to see them laying it into you down there . . . hope you’ve come out of it by now and are eating a little . . . but your family lays it into you because they love you, man; nobody understands an alcoholic. . . .”

Said my mother: “I wasn’t proud when Daddy found a man to befriend whose writing glorified an even-worse home life.”

On one of Lafe’s solo expeditions to Los Angeles he brought a Bobbie Brooks dream outfit back for Niki: a ribbed yellow wool sweater with matching plaid skirt. “A weird choice for the Southern California climate but I rarely had storebought clothes, so a name-brand outfit was thrilling,” she wrote to me. “My mother surely recognized it as reparations, but to me it was an unexpected gift of love.” When she outgrew the outfit, Niki sent it to Marina Bukowski, Charles’s daughter. “Thanks plenty for the clothes for Marina,” Bukowski wrote. “She doesn’t have much to wear, I suppose I should do better, but anyhow the clothes and purses, all that great stuff will be put to a mighty use: to make a beautiful little girl more beautiful. thank you, friend.”

3. Southern California 1970–72

A few days after the Sixth Annual Praise Bukowski Night at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York, I met my uncle Geoffrey in Chinatown to retrieve a photograph he’d brought down from his home in Great Barrington. The night at the Bowery featured writers drunk on the Bukowski myth—all ejaculation and limp cock and dingleberry. Was that really the man?

The picture showed a young man reclining with a beer, dated August 1964, and it had pervy doodles drawn on the back. Man and doodle were both recognizable as Bukowski. In the spring of 1971, Geoffrey told me, he’d gone to a reading at the University of New Mexico at which Bukowski had sat alone at a table onstage, a half-quart of beer by his side. After the reading Geoffrey had introduced himself as the son of Lafe Young.

“You got a great old man,” Bukowski said.

A year earlier Bukowski had given one of his first readings at Pomona College, brought there by the painter Guy Williams. Lafe had driven to Pomona from San Diego to hear the reading, and he vanished for several days following it without sending word to his family. “He disappeared now and then, and it was always bad news,” my mother tells me. “Anxiety. Nothing special.” It turned out that Lafe had holed up with Bukowski at the poet’s apartment on DeLongpre Avenue in Los Angeles, doing whatever they did for three days before returning home.

Skip forward. Two years after the Pomona reading, Geoffrey co-edited an issue of the magazine Stooge with Allen Schiller. Schiller’s idea was to do a box of broadsides, put the broadsides in an empty pizza box, decorate each one by hand, and call it Issue Nine. The issue included a poem by Bukowski, and because, according to Geoffrey, the boxes were “unwieldy to pack and ship” (no kidding), Geoffrey asked if he and his young wife could swing by and drop off Bukowski’s copy at his house:

We knocked on the door of his nondescript house in a typical So-Cal court of same-size-and-shape houses. He ushered us into the living room, where immediately we noticed a huge pyramid of beer cans in front of one wall. Hamm's, I think. Hundreds of cans. My thought was, No, it can’t be, the college kid routine? There were no signs of a desk, paper, or books in this room, however. Typewriter, table, and manuscripts must have been in his bedroom.

Then we showed him the issue. Soon enough he said he had to go pick up his car at the service station, and could we give him a ride. A mile later he was getting out at the gas station, and we said good-bye. I remember his friendly farewell, then him striding away from the car almost as if he were a dancer. It was all in those first few steps. He wasn’t yet beer-bellied—this was 1972, he wore a light sportcoat, scuffed brown shoes—and I liked the smooth rhythm of his gait. I had expected ungainliness, for some reason; he seemed lithe, almost athletic. And he was sober.

4. The specialist

The metaphor that would have occurred to me at 13 was this. In early Nintendo games a character in failing health appears onscreen as a blinking, faded image. This is about the level of vibrancy a deceased grandfather can have in the mind of a preteen who never knew him. Anyone’s idea of anyone is incomplete, naturally, but there are degrees of incompleteness, and my degree when I found Living on Luck felt too great. The letters helped. Talking with relatives and looking at photographs helped. Knowing the coordinates of where my grandfather was on a certain date filled in the picture, slightly, as did knowing who he was with. Little things.

The night at the Bowery Poetry Club was designated to celebrate Bukowski the writer, not Bukowski the slob of a man. You can choose the way you think about a person whom you did not know well, but you cannot choose the way you think about family. In Lafe’s case I sit somewhere between these two points. My grandfather had a higher percentage of flaws than most people, and treated his wife and children unforgivably for many years. “I don’t know if you ever met L.Y.,” Bukowski wrote to John Martin in 1971, “but he’s one of the finest people I’ve ever met.”

Molly Young's writing has appeared in n+1 and the New York Observer.