Every Thing In It

“Plomeydongs” and other treasures from the Shel Silverstein archive.

BY Delaney Hall

“He wrote on everything,” says archivist Joy Kingsolver. She has pulled a flat box labeled “Work in Progress” down from a shelf, set it on a table, and—pushing her gold-rimmed glasses up the ridge of her nose—opened it to reveal a heap of scrap paper covered with narrow, urgent handwriting. “He wrote on menus, napkins, restaurant placemats, paperbacks. Anything that was available.” She leafs through the box and picks up a bank deposit slip. In the upper left-hand corner, it reads SHEL SILVERSTEIN in blocky type. A few lines of lyrics are scrawled across it: a quick sketch for a song—or maybe a poem—about a bank robbery.

This little piece of paper is one of Joy’s favorite artifacts in the whole Silverstein Archive, a collection of the author’s manuscripts, sketches, demo recordings, and ephemera that she helps to oversee. “I imagine him standing in line at the bank, bored, and composing it,” she says. “He just continuously wrote and wrote and wrote. There’s a constant creative flow. It never seemed to stop.”

Most of the physical relics of Silverstein’s restless creative energy—which fueled his work as a globe-trotting Playboy cartoonist, an iconic children’s author, and a songwriter for the likes of Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, and Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show—are held in this archive, housed in a big, chilly room on the sixth floor of a windowless warehouse on the near southwest side of Chicago, Silverstein’s hometown. Nearby, there’s a mattress store, a muffler shop, a chain-link fence trimmed with disintegrating plastic bags. You wouldn’t suspect that the imposing industrial building holds all the stuff gathered from Silverstein’s various homes in Martha’s Vineyard, New York City, Key West, and Sausalito after he died of a heart attack in 1999 at the age of 68. But here it is.

The collection is maintained and managed by Silverstein’s nephew Mitch Myers—a part-time journalist and music writer—with help from his sister, Liz Myers—a part-time yoga instructor—and Joy, an archivist by training. For over 10 years, the small team has been gradually cataloging the collection, acquiring other materials related to Silverstein’s eclectic and far-reaching life, handling licensing and copyright issues, and forging a path as a small institution that lives somewhere between a historical repository, a commercial enterprise, and a family’s labor of love.

The staff proceeds project by project, each new endeavor taking them deeper into unexplored corners of the archive. They’ve just finished a major undertaking—the posthumous publication of a new collection of poems and illustrations called Every Thing On It, released by HarperCollins in September. Though it’s not the first collection to be published since Silverstein died (Runny Babbit, a book of spoonerisms, came out in 2005)—it is the first to try to replicate the iconic style of his best-loved works, such as Where the Sidewalk Ends (1974) and A Light in the Attic (1981), which blend his defiantly silly, capering verse with his distinctively cockeyed line drawings.

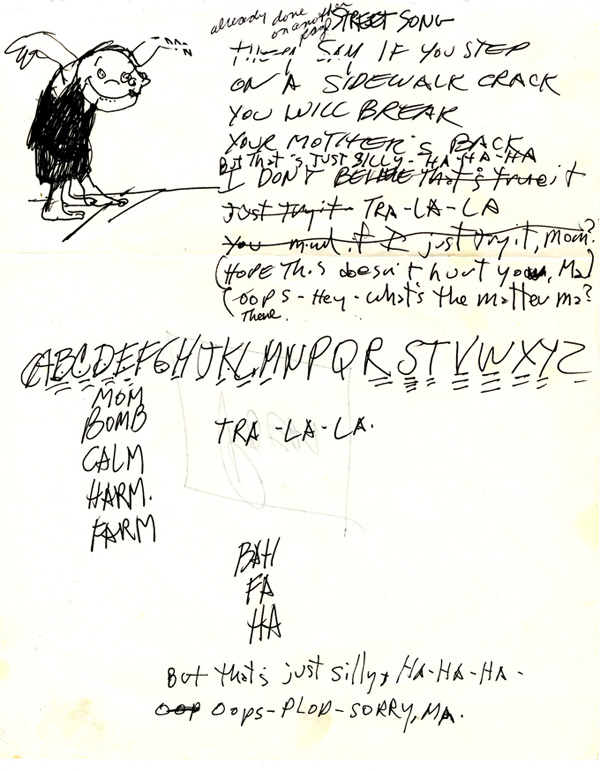

A rough sketch and draft of the poem "Sidewalking," which appeared in Falling Up (HarperCollins, 1996).

Joy continues digging through the box and then holds up another handwritten poem. “Among these scraps, we found this, which ended up in the book eventually,” she says. The poem, called “Openin’ Night,” appears in the middle of the new collection and details an actor’s disastrous theater debut, chronicled with Silverstein’s characteristic flair for accelerating mania and chaos:

She had the jitters

She had the flu

She showed up late

She missed her cue

She kicked the director

She screamed at the crew

And tripped on a prop

And fell in some goo

And then it unravels for 18 more lines. “That’s one of my favorites,” says Joy, looking fondly at the paper in her hands. “We knew it had to be in the collection.”

*

A posthumous publication can be risky—especially a posthumous publication by someone as fastidious as Silverstein. His heavily edited galleys (held here in the archive) are crisscrossed with whiteout and corrections, indicating a very hands-on style when it came to assembling his books. The careful attention he paid to the interplay between his poems and illustrations—which often riff, pun, and comment on each other—could also have proved difficult to replicate without his involvement. And then there’s the simple fact that unpublished material might be unpublished for a reason. It might not be quite as good.

Mitch, Liz, and the other members of the Silverstein Estate were certainly aware of these hazards when they set out in the fall of 2008 to compile the new collection. “We wanted it to be fantastic, of course,” Mitch says, retrieving a huge binder, about three inches thick, from a nearby shelf and slapping it emphatically. The binder holds scans of over 1,500 unpublished outtakes from previous books—poems and illustrations that Silverstein composed and laid out, but that were then cut for one reason or another. Each member of the editorial team, which included representatives of the estate and Silverstein’s editors at HarperCollins, received a binder like this one. “We sent it and we said, ‘Look at it: don’t you think there’s a book’s worth of stuff in there?’” Mitch recalls. “‘Don’t you think we could make it as good as Light in the Attic or Where the Sidewalk Ends?’” He raises his eyebrows under his black skullcap to make it clear that he asks these questions rhetorically.

All of the readers made their way through their binders and sorted the poems into categories of Yes, Maybe, and No. The team then met in New York once a month for more than a year, whittling the selections down to the final 145 and finally sequencing them. It took eight or nine passes to get the manuscript into publishable form, says Liz, a tan woman with dark curly hair. She flips to the end of Every Thing On It and points out the last poem in the collection, called “When I Am Gone”:

When I am gone what will you do?

Who will write and draw for you?

Someone smarter—someone new?

Someone better—maybe YOU!

Liz explains that during the editorial team’s final meeting, they sat around a big table and read each poem aloud to each other. “When we got to the end of the book, every person who started to read this last poem cried” and failed to get through the short stanza, she says. “And then someone would say, ‘Oh, I can do it, I can do it!’ And then no, they could not.”

*

Every Thing On It feels true to Silverstein’s previous work—from its playful cover, which shows a worried kid holding a hot dog heaped with a teetering pile of junk (“I asked for a hot dog / With everything on it,” that poem begins) to the author’s disconcerting head shot on the back, in which he looks more like a grumpy pirate or a boozy dockworker than the beloved “Uncle Shelby,” as he called his poetic alter ego. The verse inside the covers brims with the same rowdy, dark, fanciful sensibilities that characterized earlier collections and earned him a place beside children’s writers such as Maurice Sendak and Theodore Geisel (better known as Dr. Seuss). These writers shared a similarly subversive bent and favored ambiguous parables and sheer silliness over easy morality tales. Like them, Silverstein reveled in the absurdity, disobedience, and messiness of childhood.

The subjects tackled in Every Thing On It include snot, cheating, wrestling, cannibalism, adoption, monsters, and elephant and pelican excrement. A man ingests a hippopotamus, a lunatic uncle destroys a house, and a guy sells disembodied heads. One poem is titled “Burpin’ Ben” and another “Why I’m Screamin’.” But balancing the bedlam are existential poems such as “Dollhouse,” which explores the inevitability of growing up, and “The Clock Man,” which frankly addresses mortality and the fact that time, by virtue of its scarcity, is precious. In “After”—one of the gentlest poems in the collection and a kind of haiku fairy tale—snow thaws, a hand sprouts from the ground and then points a child in the direction of home.

*

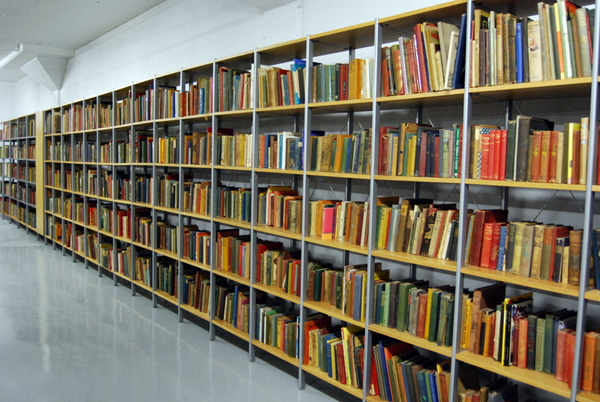

Though he resisted the moralizing tone of many classic fairy tales, Silverstein was a student and collector of the genre. Long shelves run along two walls of the Silverstein Archive, holding his detailed collection of thousands of children’s books from all over the world: Java Jungle Tales, The Golden Asses of Lucius Apuleius, Tales from a Finnish Tupa. All are hardback, but frayed and fading; most date to the late 1800s and the first decades of the 1900s. Mitch says his uncle accumulated them when he traveled, which he did widely as an itinerant correspondent and illustrator for Playboy in the 1950s and ‘60s. Photos from these years show him naked and smoking a cigar with three women at the Sunny Rest Resort nudist colony in Palmerton, Pennsylvania, and singing with Papa Bue’s Bearded Viking New Orleans Danish Jazz Band in Copenhagen, but he must’ve been sneaking away to buy rare children’s books during quiet moments. “I think he wanted to give kids a sense of life as a fairy tale, but a dark one,” Mitch says. “He didn’t want to whitewash things. Or leave kids unprepared to deal with trouble.”

Mitch takes me on toward the media room. Along the way, we pass shelves that hold copies of A Light in the Attic and Don’t Bump the Glump! translated into Korean and Chinese (“Who knows if they’re any good,” Mitch jokes), boxes of Silverstein’s genre-defying “plomeydongs” (poem/song/play/dance performance pieces), and a section dedicated to records and films that include his contributions. To hear Mitch list just a few of these is to begin to understand his uncle’s rippling and unpredictable artistic influence. His songs have been sampled by Fatboy Slim and covered by Pearl Jam, Andrew Bird, and My Morning Jacket. The Thelma & Louise soundtrack featured his “Ballad of Lucy Jordan,” and he collaborated on much of the music for I’m Not Rappaport, Herb Gardner’s film about, according to Mitch, “two grumpy old guys sitting on a bench.”

The media room holds Silverstein’s collection of LPs—mostly country, rock and roll, jazz, and comedy. Two old guitars, a dented saxophone, and what turns out to be some kind of ancient vegetable peeler (not a percussion instrument after all) sit on a shelf. This room also contains the archive’s current project, which occupies much of the staff’s time now that Every Thing On It has been published and the wave of book marketing has subsided. Over the past year, Mitch, Liz, and Joy have been working to digitize and identify hundreds of Silverstein’s demo tapes and home recordings.

Silverstein was an avid collaborator, and so this digitization hasn’t proved easy. For every well-known song such as “A Boy Named Sue,” made famous by Johnny Cash, there are dozens of unidentified recordings of Silverstein riffing and goofing in his apartment in Greenwich Village or laying down demos in a Nashville studio with some friends.

Mitch picks up one of the CDs he’s been researching recently and pops it into his laptop. “Let’s see if there’s something listenable,” he says. Silverstein’s voice warbles out of the tinny speakers, rising over the hiss of old reel-to-reel tape. “And this is starting to feeeeeeeel, a little too much like hoooome,” he sings in a voice that’s part choked bluesman and part Comiskey Park hot dog vendor, a job he held as a teenager growing up in Chicago. “He’s just free associating lyrics here,” Mitch says, listening. “This is a little different than a lot of the discs we have in that there’s no group, just fragments of ideas.”

Mitch listens to dozens of tracks like this a day, trying to determine if his uncle wrote the music, if it’s copyrighted, and who else might have contributed to the accompaniment or vocals. He says that no one was familiar with the extent of his uncle’s songwriting before the archive began digging into his old tapes. “We’re buying 45s, ferreting out co-writes, getting copies of things that no one realized even existed or mattered,” he says. In the background, Silverstein strums his guitar and muses on piña coladas.

The archive doesn’t necessarily plan to release any of these unpublished tracks, Mitch says, though they haven’t ruled it out entirely. For now, they’re still wading through the collection and trying to figure out what exactly they’ve inherited. The process of cataloging has been partly one of getting to know his uncle better. “It’s been emotional,” he says. “You make connections; you learn new things about him every day.”

One of the things you learn is that “polymath” doesn’t even begin to describe Silverstein. His creativity extended in so many directions that his archivists must be versed not just in turn-of-the-century world children’s literature, but Waylon Jennings’s deep cuts; not just in reel-to-reel tape preservation, but how to keep an old restaurant napkin scribbled with lyrics from falling apart. And you also learn that Silverstein seemed to have a terrific time drawing, rhyming, and singing his way through life.

His poem “Dirty Face” from Every Thing On It begins, “Where did you get such a dirty face, / My darling dirty-faced child?” and while addressed to a grimy kid, it seems as much like a manifesto for how Silverstein approached his own limited time on the planet. The poem ends:

I got it from playing with coal in the bin

And signing my name in cement with my chin.

I got it from rolling around on the rug

And giving the horrible dog a big hug.

I got it from finding a lost silver mine

And eating sweet blackberries right off the vine.

I got it from ice cream and wrestling and tears

And from having more fun than you’ve had in years.

Delaney Hall is a reporter and radio producer. She worked for a long while with the Third Coast International Audio Festival at Chicago Public Media and she's now the Poetry Foundation's Columbia Journalism Fellow.